“The monster, for me, is the wild unknown breathing unexpectedly in the corners of the familiar. It is a queering in the ecotones of abstraction and representation, a refusal to resolve into shape or blur into formlessness. My art practice is a being-with the monster, often visually expressed through the rendering of corporeal liminality; heads blossom into ecosystems, disordered limbs tangle and transform, figures become ground for strange forces of livingdying.”

– Krista Dragomer

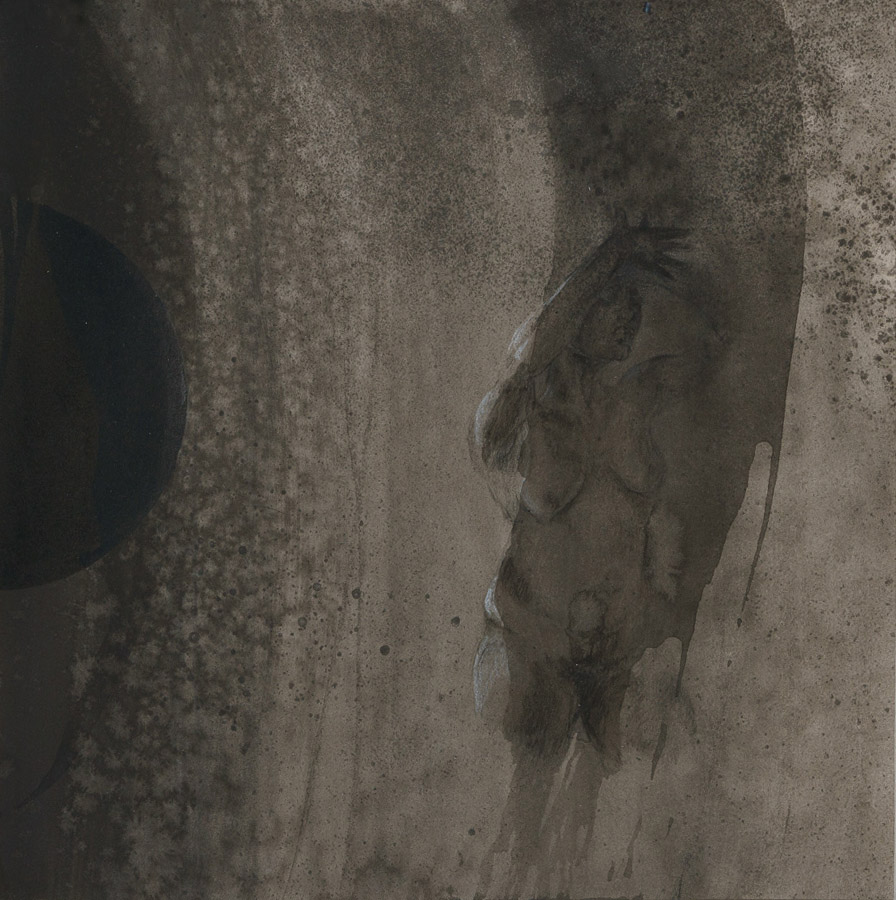

Two Faces of Light, 2021, 10”X10”, watercolor on paper.

Erin Manning: Many people think of drawing as the gesture of representing the world. This turns drawing into an arm’s length process: you look at the world, and then you reproduce its likeness. Your process refuses this separation. Did you want to say more about it?

Krista Dragomer: Yes, I like to start with that idea of drawing and then ask: but what is representation? What is world? Where do I stop and you begin? Different senses may answer these questions differently. What I might trace as the line of your cheek is the moment when your cheek is turning away from my vision. To render this moment of away-from as form, I hold the feeling of your cheek in the net of my other senses and when I draw “you”, I draw from that net that is also sensing the points of contact between my body, the chair and air and sounds everywhere. We don’t leave this field of relations to draw. In For a Pragmatics of the Useless you write “We always happen in the middle. Not first a thought, then an action, then a result, but a middling, “we” the result of a pull that captures, for an instant, how the thought was already action-like, how the body was always also a world.” This is the drawing process. There are no beginnings, no ends, only middles that tease out different conditions of our sensation and to which we, for a moment, give our attention.

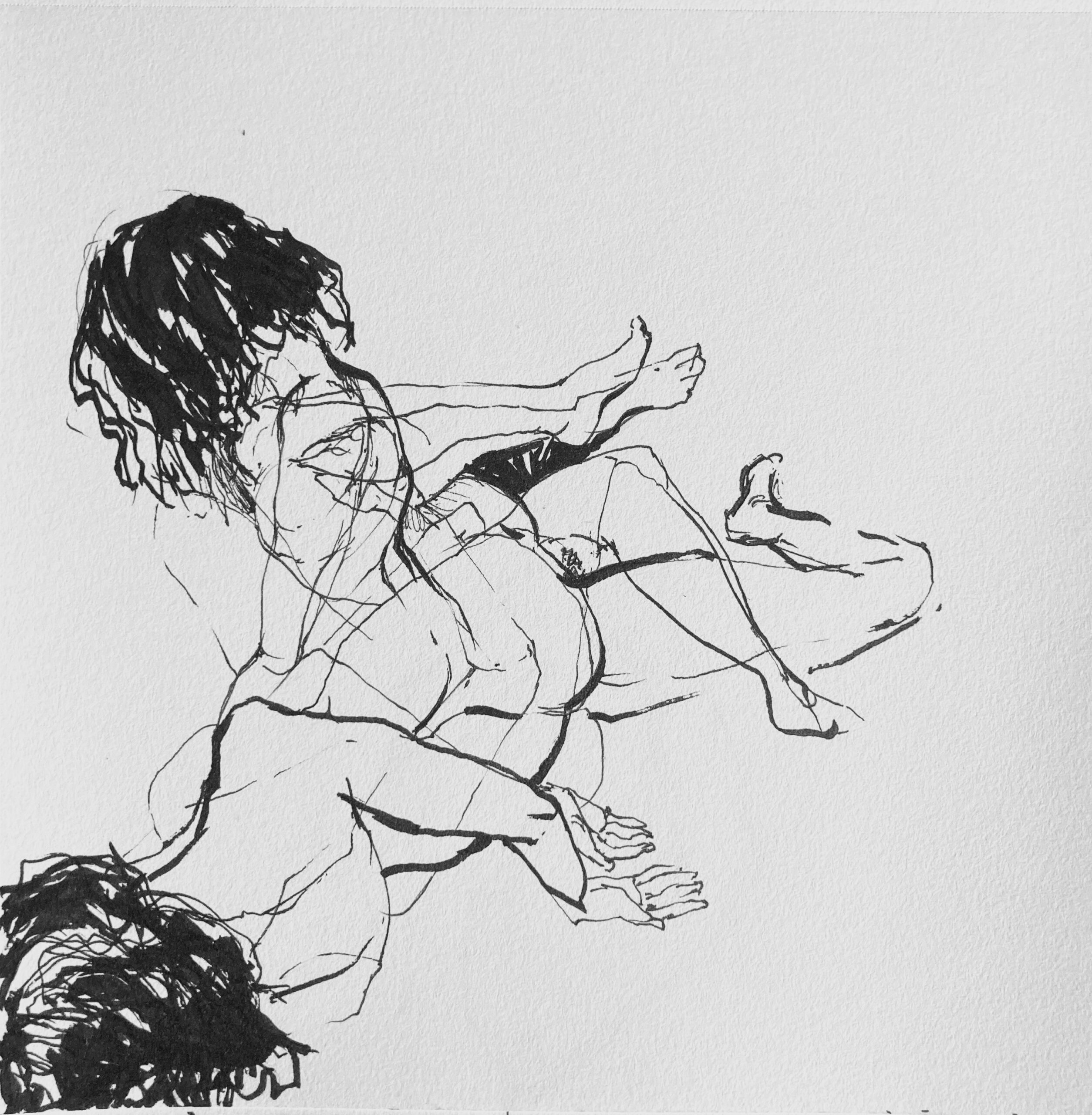

From the sketchbook of interrupted sleep, 2021. 5”x5”, ink on paper.

Rather than say more about it, let’s try drawing together. Gather some drawing materials – 2 pencils or pens and some paper – and find a place where you can sit near a plant. Take a few moments to note all of the ways that you can sense the plant. Then close your eyes and scan through your body with your interoception, noticing the feelings of sensing. With 1 pencil in each hand, follow those sensations through your body, making marks as you go. Keep your eyes closed and draw yourself sensing the plant for 3-4 minutes (you might want to set a timer or use something in your environment as a time-keeper). Now, with your eyes still closed, reach out and (gently) touch the plant. Experiment with ways to include this feeling in your drawing. When you’re ready, open your eyes and continue to draw yourself touching the plant. Include yourself and the plant in the drawing, your feeling of touching and being touched, and the feeling of the plant touching and being touched. You may want to try switching hands, and alternating between eyes open and eyes closed. Get a new sheet of paper if you wish. Notice what is differently available to you as you shift between modes of taking-in. How are the collections of marks you’ve just made a gesture of representing the world?

Erin Manning: The field of sensation is only relational. Put into a sensory-deprivation chamber, and there is no sensing. This is because there is no compass for difference: when everything is the same, there is no contrast. Sensing requires contrast. This means sensing opens us to difference. Your art touches this complexity. Can you say more about how you draw into this difference?

Krista Dragomer: In my work, I like to ask: can we experience contrast without naming? If representation is the organization of sensory information into narrative forms that correspond to collective ideas about how the world is, and abstraction is sensation without the storying of forms, is there a way of being with sensory contrast that neither supports nor denies the moments of perceptual-conceptual feeling that occur in practice, to keep it all moving but never arriving? Drawing on the lines of paraontology that you trace through your work from Fred Moten and before him Nahum Chandler, I like to call this way of being-with a pararepresentational practice. The pararepresentational is less the sense of something and more a sensitizing to the uncertain, unnamable moments that cause a shivering simultaneity of recognition and disorientation. It is the queerness that hovers around the disruptions to the orders of the known, the feelings produced by moments of incoherence within fields that predicate themselves on the maintenance of certainty. It hovers around your peripheral vision and whispers directly into your optical nerve: maybe light is more than light, maybe your eyes have other ideas of what vision could be.

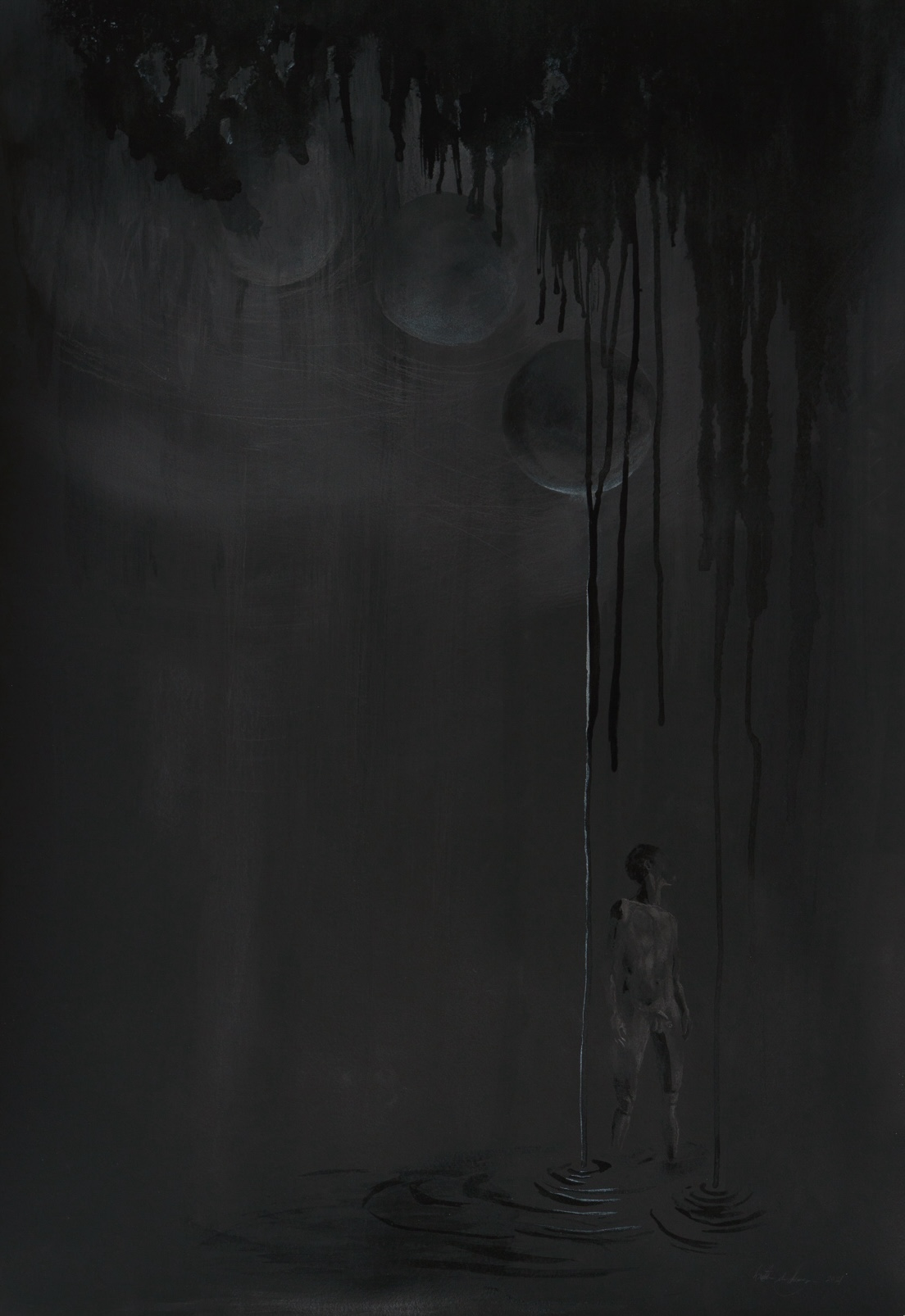

Night Rain II, 2021. 26”x32”, mixed media on paper.

One way I play with this in my practice is with figure and ground, that is the perception of a foreground and background. I’m interested not just in the entrainments that lead to discerning edges and separations between forms but in how those perceptions shape relational ethics, and how they might be drawn differently. Let’s try another drawing exercise. Place an object on a table at an arm’s length away. Tune into the space between you and that object and all that surrounds it, what we would call the background. What constitutes the background? What senses are involved? How is your body involved? What is the boundary between the object, the background, and you? Make a drawing of the space between you and the object (drawing neither you nor the object), tuning into the senses you use to perceive the object in your shared space.

Erin Manning: Your drawing process is layered. Having watched you draw, I have seen these layers form palimpsests of thought in motion. Thought need not take form in language. Could you say more about the movement of thought in your work?

Krista Dragomer: I became very aware of this when I was drawing on camera for the 2023 iteration of We Will Dance with Mountains. My thought would move in one direction and then suddenly jump to another plane, taking up a different grouping of considerations for a moment, then moving again. I might draw two toes on a foot and then switch to some blobby shape in the bottom corner of the paper before coming back to render the other toes, or not. Again it’s a middling. It isn’t a centralizing of thought, an “I” doing the making that then rolls out in a sequence of this after that. I’m not claiming it is all just generating spontaneously. There is, of course, an ecology of gestures that I have been growing and tending to for a long time – that is part of a practice – that is giving shape to the movement of thoughts. But rather than be articulated through a sense that I am carrying out a specific intention, thoughts and feelings body themselves through a responsiveness to sensory-spiritual-erotic-intellectual currents, relations, or agencies that territorialize my body into modes of making.

The pararepresentational figures 1 and 2, media on paper.

That said, I can definitely get caught up in thinking in my work. When I find myself there I ask questions like: what does intention collaborate with? How can I draw, make, or create atmospherically, in other words in a way that conditions the relations without structuring them? It isn’t that I don’t appreciate intention or structure in my work (I do!) but to notice when those elements get captured in the languaging of thought that imposes a linearity to time that points me towards conclusions rather than questions.

Art from ten’s Becoming Monster Festival.