7:17am. On the crisp morning of June 30, 1908, near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River, somewhere above about 2000 square kilometres of forest in the sparsely populated Eastern Siberian taiga, the sky cracked in two with the deafening roar of a dying god. An explosion the likes of which had never been heard of, rent the air above the vast biome, flattening 80 million trees with the force of 15-megatons of TNT. For comparison, the Hiroshima bomb (and its birthchild, the haunting mushroom cloud of ignominious memory) – representing the pinnacle of American techno-military might in the 1940s – was a thousand times less powerful, which is why the Tunguska event is considered the largest earth impact event in recorded history.

Over the years since Tunguska, the most unique event of its kind in recorded history, a plethora of explanations and theories has swirled in the air like the unsettled dust from that morning in 1908. Scientists were not allowed to the region until 1927. By then, there was an entire market of ideas bidding for public attention. The blast was usually credited to asteroid impact (though without collision, as there is no visible impact crater and no meteoric remnants). Some said a fireball rushing from the sky leaving a trail of hell in its wake and a parliament of trees pointing away from ground zero was the right way to tell the story of the event. Others pointed to the collision of matter and antimatter, an extra-terrestrial visitation, or something else celestial, paranormal and less obvious than the not-so confident official account. Even in more recent times, with more advanced technologies and paradigms at our disposal, the event resists full articulation. It is as if whatever exploded, liquefying the ground in its fury, also destroyed the possibility for intelligibility – leaving us perpetually perched at the precipice of the awkward.

In this sense, the Tunguska event is a creative way to frame the work of prophecy. When we think of prophecy and the prophet, we might retreat to biblical images of scraggly old men with sandals pontificating on the future and whispering doom stories before wide-eyed kings and petrified subjects. When I think of a prophet, I think of Tunguska. I think of the moment when the strings that hold the habitual together are loosened ever so slightly, when the dissensual blasts through a geometaphysical paradigm of sense-making. I think of prophecy as an invitation to occupy the fluid, to stay in the places where the celestial scrapes the mundane and refuses to yield its royal passage to the tools of ordinary analysis. The thin place of Celtic fascination where the otherworldly leans so heavily into the veil that removes it from the thisworldly. Postactivism is what we do in the wake of prophetic collisions, at the edges of world-ends, at the circumferences of unspeakable blasts.

Perhaps epidemiological matters and public health concerns cannot be measured in terms of megatons and kilotons and petajoules. However, I couldn’t help but think about Tunguska when earlier this year the World Health Organization confirmed that the planet was now in the grip of a pandemic. The COVID-19 phenomenon is comparable in its effects: its bodily impacts are not completely understood in spite of a full articulation of its genomic sequence; being fleetingly minute and vanishingly surreptitious in its operations, it resists the casual gaze – like a hypothesized asteroid slinging its way back into orbit. Most importantly, the thunderous roar of the pandemic was just as seismic: for a moment, it rendered the proud tarmacs of modern progress molten; it liquefied the firm grounds with which we forecasted the future; it flattened the parliaments and laid waste to our political ideologies and their pretensions to puritan exclusivity. Oil barrels sold for less than zero dollars. The pandemic not only broke our bodies and economies, it broke time.

Right now, massive reconstruction efforts are underway to restore the primacy of clock time. But there is still abundant room for prophecy. The ground is still open. Our bones are still sore. Our psyches are still out-of-whack even as the neon-lit shopping malls reopen for business. The work of prophecy is to look again, to scavenge the mushy surfaces of celestial-mundane collisions for rare ways of speaking, seeing, and politicking. What will we find when we look, when we sit with the trouble, within the rupture? What will we be shocked by when we examine the landscapes of our awkward bodies? What will we come to touch as we come to recognize the computational algorithms that have always been invisibly part of our flesh but are now visible?

Pieces of sky, obviously. Pieces of sky.

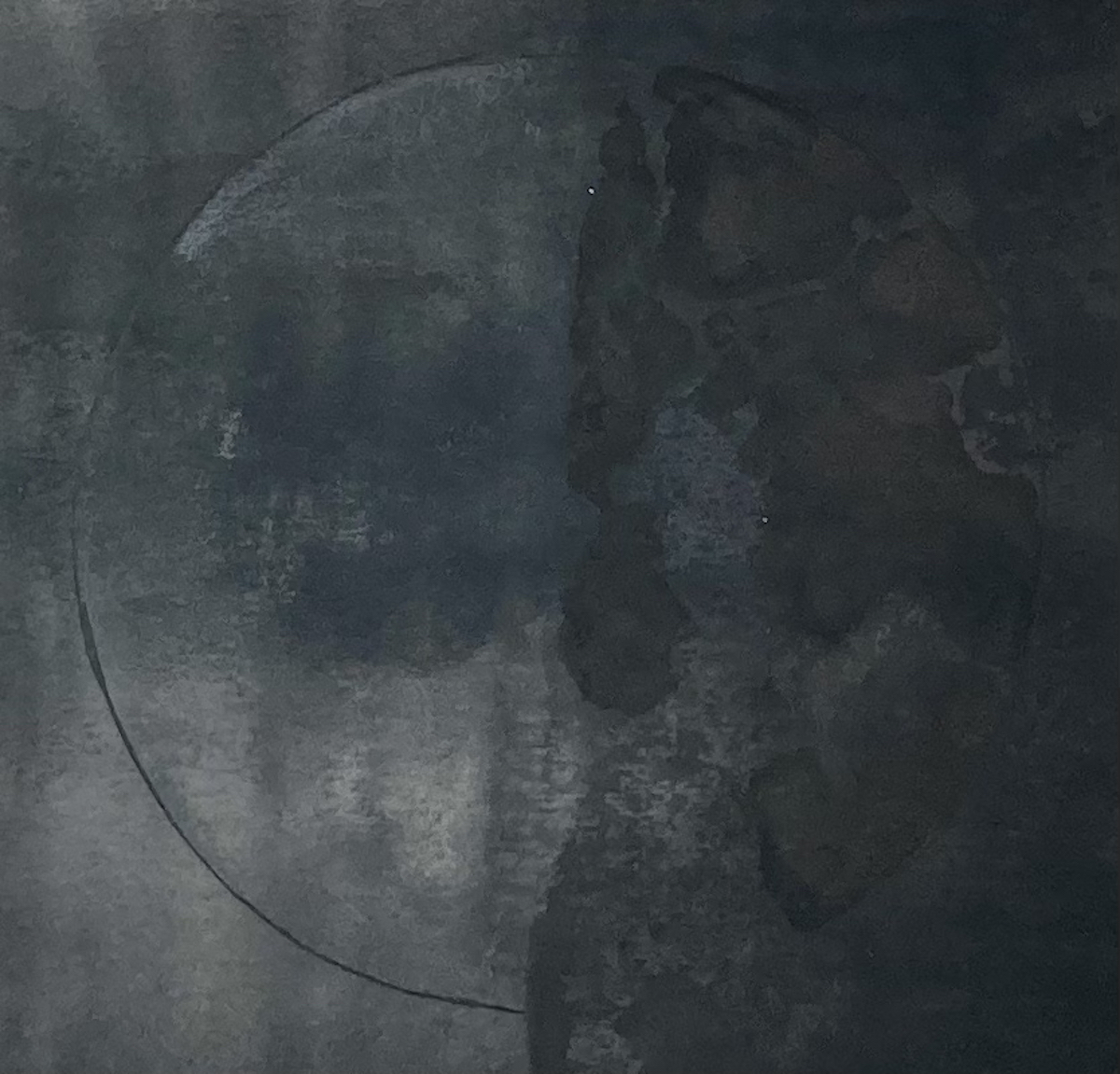

Art by Krista Dragomer.